https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-026-00089-8

Girls are starting puberty younger — why, and what are the risks?

More girls are hitting puberty at eight or earlier. Researchers are exploring the causes, the consequences and what should be done.

By

The average age at which girls start puberty has been falling. Credit: Catherine Falls/Getty

When Lola was eight years old, she went through a massive growth spurt and started developing acne. Her mother, Elise, thought Lola was just growing fast because of genes inherited from her father. But when she noticed that Lola had grown pubic hair too, she was floored.

Collection: Coming of age: the emerging science of adolescence

A visit to an endocrinologist in 2023 confirmed that Lola’s brain was already producing hormones that had kick-started puberty. Lola had also been struggling emotionally. “She would have panic attacks every day at school,” says Elise, who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and asked that her surname and Lola’s real name be omitted.

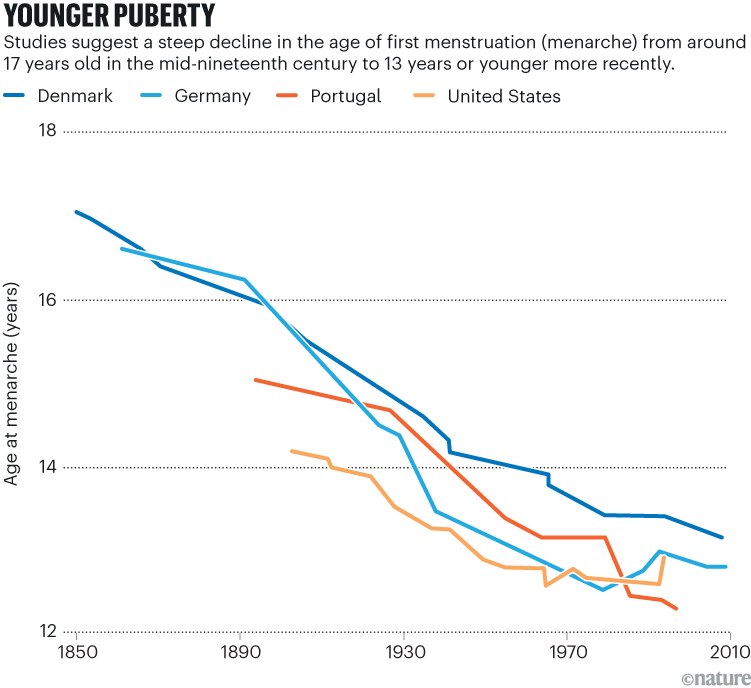

Although eight might seem young to start puberty, it’s not as rare as it once was. Data show that girls around the world are entering puberty younger than before. In the 1840s, the average age of first menstruation, or menarche, was about 16 or 17; today, it’s around 12. The average age for onset of breast development fell from 11 years in the 1960s to around 9 or 10 years in the United States by the 1990s. Some research hints that the trend mysteriously accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. (Although some data suggest that puberty is happening earlier for boys too, the shift seems to be less pronounced.)

Scientists have found a range of possible drivers for this change, with increasing body weight and obesity almost certainly playing a part. Some researchers suspect that exposure to hormone-disrupting chemicals or stress during childhood could be pushing puberty earlier, but studies have produced conflicting results. The trend has prompted the international organization the Endocrine Society to develop clinical-practice guidelines on puberty, to be published in mid-2026. The guidelines will reconsider how to treat girls on the border between typical and ‘precocious’ puberty, which has commonly been defined as before the age of eight in girls, but that some specialists argue should be younger.

Research over the past few years is also making the health risks of early puberty increasingly clear. Studies have linked it to greater risk of conditions including obesity, heart disease, breast cancer, depression and anxiety. Other research suggests that children who go through puberty earlier are more likely to experience discrimination because of their race or ethnicity, or otherwise be treated differently from their peers.

Families, researchers and clinicians are now trying to work out how best to adapt and when to intervene. This might involve medications to pause the process, but also better support and puberty education for children to protect them from some of the psychological and social risks. “We want to intervene right in that moment before people start internalizing some of those feelings of being othered,” says Michael Curtis, a family social scientist at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

New normal

Technically, puberty begins when the brain’s hypothalamus begins producing pulses of gondatropin-releasing hormone. What triggers this process isn’t fully understood — it’s probably a complex interaction between genes and environmental factors. But the result is a hormonal cascade that leads to the release of the sex hormones oestrogen (in girls) and testosterone (in boys), which drive physical changes, including menarche. (The binary terms ‘girls’ and ‘boys’ are used in this article to reflect language used in studies and by interviewees.)

The drop in average age of menarche from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century is often attributed to improvements in health, such as reductions in infectious disease and malnutrition (see ‘Younger puberty’). This probably sped up growth and sexual maturation. Most researchers assumed that the timing of puberty had remained relatively stable since then. “Studies from the 1960s showed that it was kind of levelling off at 12 and a half years,” says Paul Kaplowitz, a retired paediatric endocrinologist who was at Children’s National Hospital in Arlington, Virginia.

Source: K. Sørensen et al. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 77, 137–145 (2012).

In 1969, British paediatrician James Tanner and biologist William Marshall reported one of the most comprehensive studies1 of puberty’s timing as part of a two-decade study at a children’s home in Harpenden, UK. They observed that breast development is the first outward sign of puberty in girls and that it begins around 11 years old, on average. (For boys, the onset of puberty2 was closer to 12.) The ‘Tanner stages’, which demarcate five stages of progress towards sexual maturity, became widely used in medicine and research.

By the late 1980s, however, Marcia Herman-Giddens was questioning Tanner’s timings. As part of her work as a physician’s associate at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, Herman-Giddens had examined thousands of girls in the United States and observed that some were developing breasts and pubic hair “way younger than the Tanner standards”, she says.

Herman-Giddens and her team set out to develop benchmarks for US children. With the help of physicians from across the country, they collected data on pubertal timing from around 17,000 girls who had undergone physical examinations in physician offices between 1992 and 1993. This showed that the mean age at which breast development started was just under ten years old for white girls and nine years for Black girls. It was the first large study to suggest that puberty was beginning much earlier than Tanner had suggested, at least in the United States.

Do smartphones and social media really harm teens’ mental health?

In 1997, when the team’s findings were published3 the reaction among the scientific community was, largely, disbelief. Anders Juul, a paediatric endocrinologist at the University of Copenhagen, didn’t see similar figures in Denmark and, with obesity on the rise, he suspected that US physicians had mistaken fat tissue for growing breasts.

In 2002, however, a second US study reached a similar conclusion4 to Herman-Giddens. And in 2009, Juul and his team reported5 that the mean age of breast development in Copenhagen had fallen from just under 11 years in the early 1990s to just under 10 in the mid-2000s. The change couldn’t be attributed to increased weight, because the girls’ body mass index (BMI) had not changed. “To our surprise, there were no differences in obesity between the old cohort and the more contemporary cohort,” he says.

A 2020 meta-analysis of 30 studies6 — and the most recent comprehensive review of global trends — revealed that the median age of breast development fell by almost three months each decade between 1977 and 2013. The United States had the earliest onset (a median of 8.8–10.3 years), Africa had the latest (10.1–13.2 years) and Europe and Asia fell in between. An update7 to this study, presented at a 2025 European endocrinology meeting, shows that the trend has continued.

Researchers don’t know whether puberty will continue occurring even earlier or at what point it might hit a biological floor. Globally, physicians now typically consider puberty onset between the ages of 8 and 13 in girls as in the normal range.

Puberty puzzle

For years, researchers have been trying to work out why puberty is starting earlier. Of their handful of plausible hypotheses, the worsening obesity epidemic tops the list.

Globally, obesity rates have risen from around 2% of children and adolescents in 1990 to around 8% in 2022, and from around 11% to more than 20% in the United States, according to the World Health Organization. A 2022 study8 of nearly 130,000 US children found a clear association between obesity and earlier puberty in children. “It is beyond any doubt that obesity is a major driver,” says geneticist John Perry, who studies growth and reproduction at the University of Cambridge, UK.

One way in which body weight influences puberty is through leptin, a hormone produced by fat cells. This can interact with the brain circuits that control development and reproduction. “We don’t think that leptin initiates puberty,” Kaplowitz says. “But it’s important for puberty to progress.”

Who exactly counts as an adolescent?

Other researchers, including Juul, suspect that hormone-disrupting chemicals in the environment could be at least partly responsible for advancing puberty. They point in particular to chemicals found in plastics, such as phthalates, forever chemicals called PFAS and synthetic fragrances, all of which gained widespread use in the twentieth century. These compounds can interfere with hormones by mimicking them or disrupting their activity. But results are inconsistent, and proving a link to any single substance has been incredibly difficult. “There haven’t been really any good studies that have shown this in a way that everybody says, ‘yep, that’s the answer’,” Kaplowitz says.

A third possible piece of the puzzle is psychological stress. Some research suggests that girls who encounter stressors such as domestic violence, abuse, poverty and discrimination are more likely to start puberty at a younger age than those who do not. One 2022 longitudinal study9 found that physical or emotional abuse in early life was linked to earlier menarche in US girls.

Stress doesn’t necessarily explain the population-wide shift in the timing of puberty — there’s no rise in childhood stressors that clearly matches the downward trend in the onset of puberty. But it might interact with excess body weight, says Lauren Houghton, an epidemiologist at Columbia University in New York City. Her unpublished research suggests that girls who experience high levels of stress, have elevated stress hormones and a high BMI start developing breasts, on average, seven months earlier than do girls who experience low levels of stress and have a low BMI.

Stress might also be a reason why more girls entered puberty early during the COVID-19 pandemic than in the years preceding it. Soon after the pandemic began in 2020, paediatric endocrinologists in Italy noticed that the number of referrals for precocious puberty soared. They later reported10 that 41% of those referred in 2020 met the criteria for the condition, compared with 26% in 2019. Studies from other countries have revealed a similar phenomenon and some suggest that puberty progressed faster too11. We saw “truncated and shorter puberty”, says Louise Greenspan, a paediatric endocrinologist at Kaiser Permanente San Francisco in California.

The reasons for this are difficult to parse. With schools closed, children in many countries spent more time on screens. They exercised less, and some gained weight. But Greenspan has a hunch that it was the stress of the pandemic that affected puberty. “We’re talking about chronic, low-grade stress. I think that that did affect our kids.”

Ultimately, the causes of advancing puberty are likely to be complex and interacting, which is why Herman-Giddens doesn’t expect to find a clear explanation anytime soon. “There will never be a way to tease out all the factors that contribute to the onset of puberty,” she says.

Serious stakes

A growing body of literature, meanwhile, suggests that early puberty is linked to a higher risk of some chronic diseases during adolescence and later life. For instance, epidemiological studies show that earlier menarche is strongly associated with an increased risk of adult type 2 diabetes12. But, says Perry, researchers do not know whether the timing of puberty influences diabetes, imminent diabetes influences the onset of puberty or — more likely — a third factor, such as obesity, might affect both.

Perry has been working to untangle some of these associations using Mendelian randomization, an epidemiological technique that helps to distinguish cause and effect. One such study13 reported in 2017 that early puberty causes increased risk of breast and endometrial cancer, independent of BMI. Part of the explanation could be that early puberty increases a woman’s lifetime exposure to oestrogen, which boosts breast cancer risk.

Studies suggest that girls who enter puberty earlier than most of their peers are also at heightened risk of a variety of mental-health and behavioural conditions, including depression, anxiety, eating disorders and substance misuse. That could be the result of reproductive hormones acting early on key emotional and cognitive centres in the brain.

Why kids need to take more risks: science reveals the benefits of wild, free play

But a growing body of literature suggests that the link has more to do with children’s changing bodies. People respond to and interact differently with girls who are taller and have signs of puberty, such as developing breasts, says Rona Carter, a psychologist who studies pubertal development at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Girls might feel pressured to act more mature and independent, and miss out on some of the nurturing that childhood provides. And because Black girls develop earliest, they are often the first to feel the impact. Adults view them as “a little bit older, less innocent, not needing support”, Carter says.

A longitudinal study14 published in October found that early puberty was associated with increased racial discrimination in Black and Latinx girls, but not boys. This might be because pubertal changes are more visible in girls, making them more likely to be objectified or negatively stereotyped.

A positive social environment, however, might protect children from some risks linked to early puberty. In June, a team from Australia reported15 that factors such as family support and acceptance, supportive friends and a positive school environment predicted less rule-breaking and depression in girls entering puberty early.

Carter thinks that simply preparing children for puberty, and potential reactions to it, earlier and better could have a shielding effect. “There’s a lot of anticipatory anxiety around puberty — girls not knowing what to expect, parents uncomfortable with talking about it,” she says. She developed Double Digits, a puberty education programme for Black girls aged 9–11 years old. It provides practical information about menstruation products and hygiene and involves discussions about bias that they might experience. “How can we help them spot potential ways that they could be adultified? How can they respond to that?” says Carter, who has been running the programme at an elementary school in Ypsilanti, Michigan, since 2018.

There is a medical option, too. Endocrinologists will sometimes prescribe hormonal suppressants known as puberty blockers to children with precocious puberty. That’s partly because such children might stop growing earlier than usual and can struggle to manage their emotions and the logistics of menstruation. “Elementary school bathrooms don’t have pads,” Greenspan says. The use of puberty blockers in children with gender dysphoria has sparked debate, but the therapy is widely accepted by specialists for some children with precocious puberty.

The falling age of puberty onset has prompted endocrinologists to debate what constitutes precocious puberty and when it should be treated — something that the new Endocrine Society guidelines might clarify. “This seven- to eight-year-old group is mostly made up of healthy, normal kids who are on the early side,” says Kaplowitz, who proposed lowering the threshold more than two decades ago.

In 2023, Lola started taking puberty blockers at the age of eight because her parents were concerned about her mental health and worried that early puberty would affect her adult height. Now almost 11, Lola will stop taking the therapy soon, and her mother, Elise, is hopeful that she’ll be able to handle puberty better now than she could a few years ago. “She’s had much more time to evolve,” she says. “I’m glad to give her a little more time.”

Nature 649, 816-818 (2026)

doi: Girls are starting puberty younger — why, and what are the risks?

Last edited by @suen 2026-01-22T08:01:45Z