“I’m Pike Malinowski, and you’re listening to the Louisiana Literature Podcast. Who am I? What’s the meaning of being human?

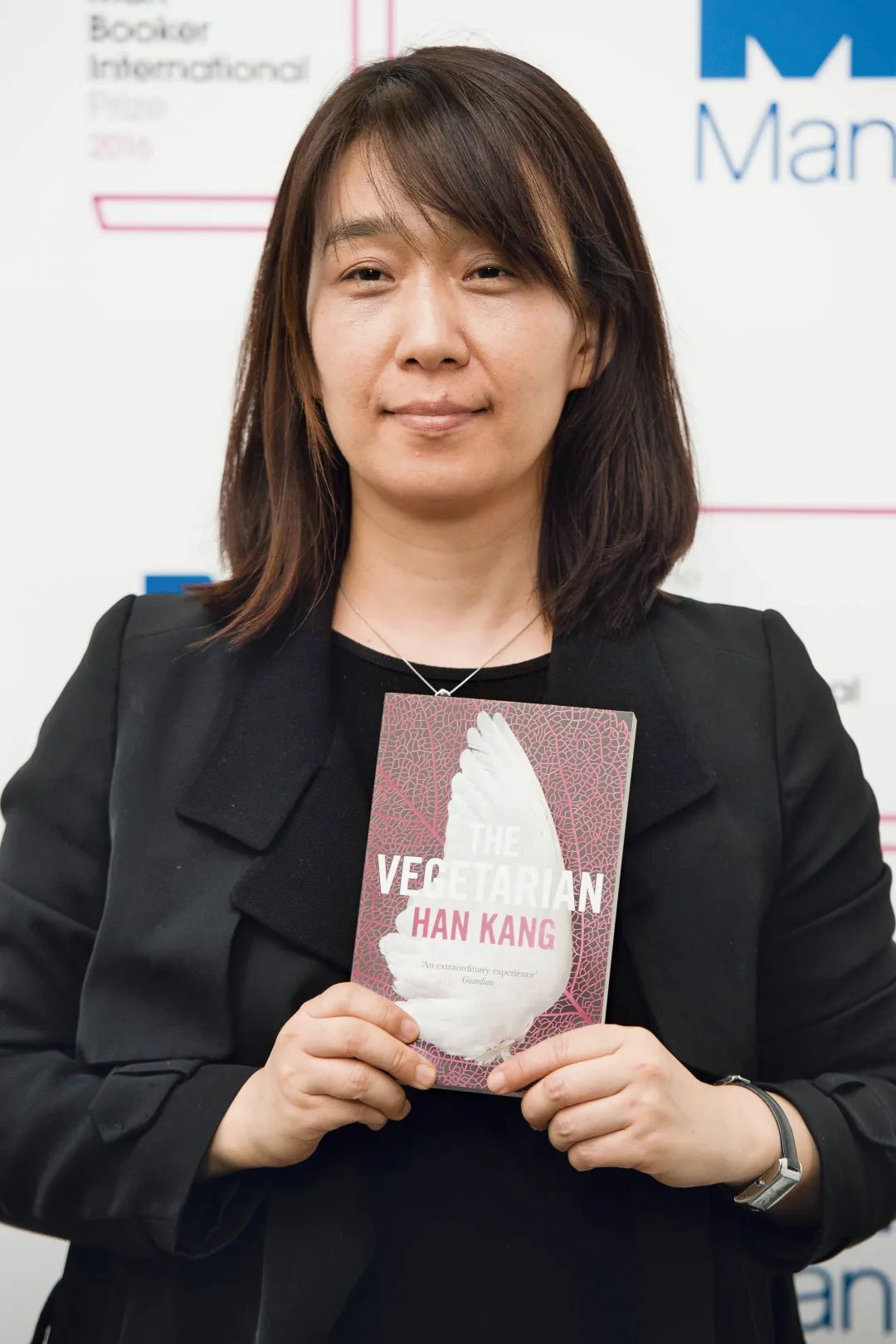

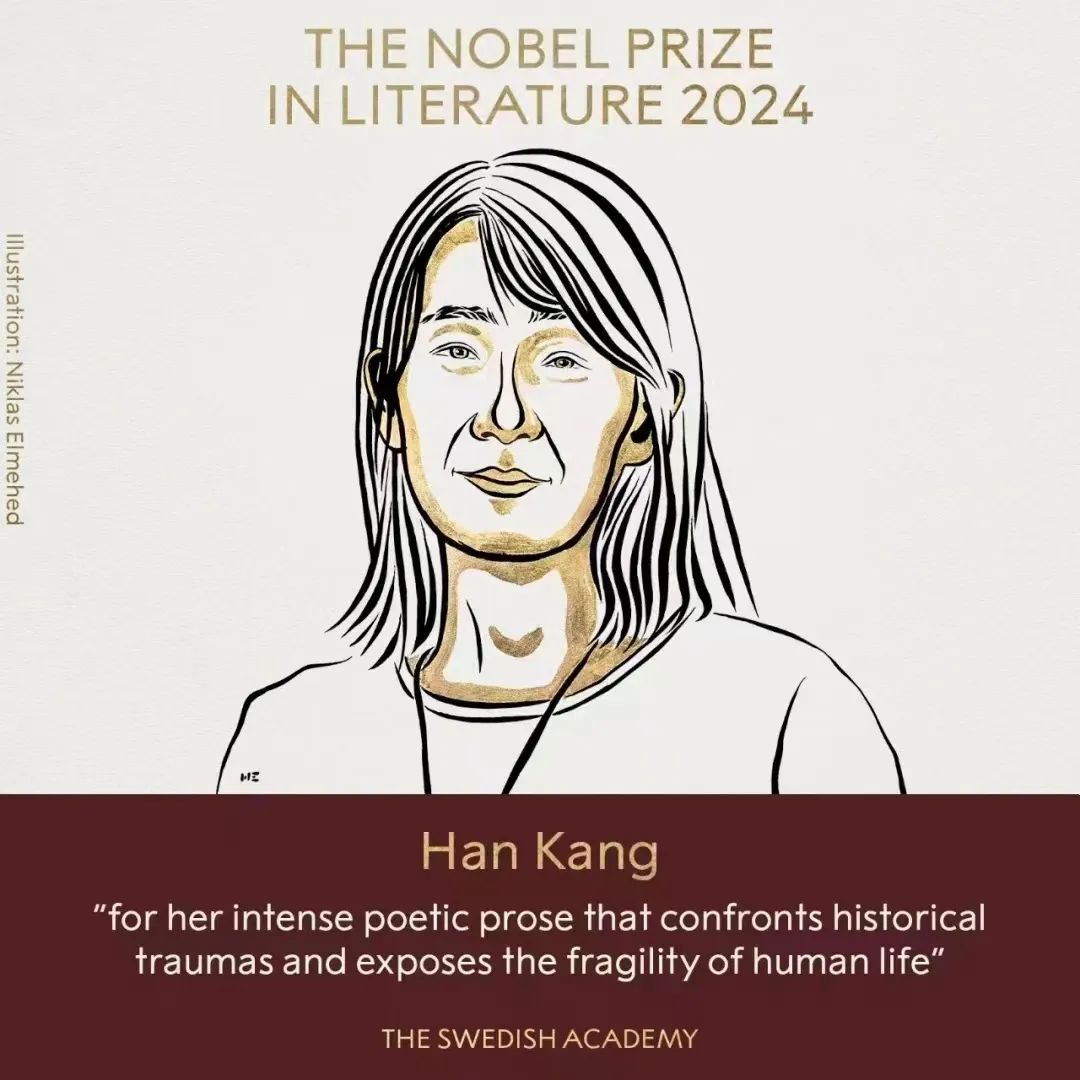

South Korean poet and novelist Han Kang confronts these questions with her country’s violent history.

Since when I was a child, it was very overwhelming to look at all the things human beings have committed throughout the history and throughout the world.

Han Kang grew up in Gwangju, a city of one and a half million people in the south of the Korean Peninsula. A few months after she and her family moved to the capital of Seoul, Gwangju experienced a student uprising against the martial law government, in which hundreds of students were massacred and killed.

You know, humanity has such a broad spectrum. I’ve always wanted to know the meaning.

In this intimate interview, Han Kang speaks about how literature helps to pierce her distrust in human beings, and about her sixth novel, The Human Acts, in which the 12-day massacre is the violent center.”

“So, when I was a child, my father was a very young novelist. It meant we were poor, and we had to move a lot, and we didn’t have much furniture, but we had a lot of books. It was kind of a private library, and it is like being protected by books and surrounded by books.

And for me, books were like a creature, expanding, because the number of the books were increasing week by week, month by month, so it was like living with them. And I attended five primary schools, which could be quite much for a child. But I don’t remember, I felt hurt, maybe because I was protected by all the books.

And I spent all month reading books in the afternoon, until I make friends, made friends. So, it is a very precious memory. And I remember one day, I was reading a book, and I couldn’t see the lines.

I couldn’t see anything. And what happened, and I realized it has become dark. So I had to turn on the light, and I just kept reading on.”

“And so I discovered books just as pure joy. And afterwards, I became a teenager, and I was confronted by very typical teenager’s questions, like, who am I, what I can do in this world, and why everyone has to die, why human pains exist, or what are human beings, and what is the meaning of being human? And then, I wanted to search these questions, and I kind of revisited all the books in a new way, and I felt I was, can I say, by accompanying the writers’ questioning, and everything was new at the time.

And at a certain point, I wanted to become a writer. I remember the day when I decided to myself to become a writer. It was when I was 14.

I just wanted to write my questions, and at the age, writers are kind of collective, and they were surrounding me together, and they were searching and questioning, and sometimes they felt helpless, clueless. I just wanted to be with them because I was helpless and clueless. At the time, I just started to write some lines.”

“Maybe they were similar to some poem. I’m not sure. I just wrote some sentences or phrases, even sometimes just words.

And I started to write journal. Until now, I write journal, not every day, but sometimes. So that was all.

I didn’t start to write fiction at the time. I started to write fiction since when I was 19. And it started with a very short story.

And then I moved to a little longer story. And I published some short stories at literary magazines. And I worked as an editor and a journalist for three years after I graduated from university.

And I really wanted to write my first novel, so I quit. And it took three years to finish my first novel. And from then, I have written novels, short stories, and poems as well.

So it’s not like I decide to write poems. They just come. And even when I write fiction, poems just come into the fiction.

It’s like an intrusion. So, yeah, language is something I have to struggle with, maybe till the end. And there are questions I have had for a long time.”

“No, since when I was a child, it was very overwhelming to look at human beings, you know, all the things human beings have committed throughout the history and throughout the world. And at the same time, you can see such dignified human beings all around the world. So, it was like impossible reader for me.

And the fact I belong to this human race, and you know, when we are confronted by the horror of humanity, we have to question what is the meaning that we are human. You know, humanity has such broad spectrum. I always wanted to know the meaning.

Yeah, so, it is like unending inner struggle, because I want to embrace this world and embrace life. But certainly, there are points we cannot, and it’s like walking back and forth between these two riddles. It’s like all my life.

But I, I have this medium, my language, and with this, I have to move forward. In 1980, there was an uprising against martial law declared by new military dictatorship in South Korean peninsula.

And, the states killed the people who were against them. And there happened a civilian autonomy. And it lasted for ten days”

“And finally, the troops came back to the city, and they killed again. So, we can call it a massacre. And a rising and absolute community.

I see Gwangju, the name of the city, not as a specific city. For me, it’s like a fundamental name or a fundamental noun for humanity, which has these two extremes, from sublimity to the horror or to the basement. So I can see everywhere Gwangju, whenever we are confronted by these two extremes.

So I wanted to write about that Gwangju, which is coming back to us over and over again. We don’t know how many people were killed. And officially, it is 200 and some more.

But there are many people who are missing until now. So we don’t know yet.

But is it thousands, you think?

I think so. But I cannot say because we don’t know the truth. I was born in Gwangju, and my family left Gwangju in 1980.

It was January. It was so cold. So it was a very cold day.

So I remember even the date. It was the 26th of January. And we just left the city because my father had quit his teaching job”

“To become a full-time writer. And he said, now I don’t have a regular job, so why don’t we live in the capital? It was a very spontaneous decision.

And we moved. And after four months, the massacre occurred in Gwangju. Till then, Gwangju was just a small city with some universities, quiet, peaceful.

Suddenly, the connotation of the city has become really different, and nobody imagined that massacre. And we can call it an uprising, and we can call it absolute community of solidarity. And it was like long period of sense of guilt for all my family.

We didn’t leave the place intentionally, but it was like that. So it was the feeling that some people were hurt instead of us. And it was inside myself for a long time, even though I didn’t plan to write about it, never.

Just I grew up with this memory which I experienced indirectly, and it stayed in my nightmares. And suddenly after I finished my fifth novel, I wanted to capture the reason why it is so difficult for me to embrace this world or life. And I had to dig into myself deeper and deeper.”

“And then finally realized that I had to penetrate this doubt about human beings through writing. And so, that was why I started to write human acts. And during the process of collecting all the materials, I was even more shaken and torn, because I had to witness all the atrocities.

I read a very big book of testimony of 900 people who survived, or were injured, or were bereaved. And it was like collecting all the fragments all together, because I didn’t want to write a cold book with the evident, you know, incidents. So, more I read, more I lost my trust, and at some point, I realized that I was dealing with some people who were so dignified in front of human violence, and there were people who donated their blood to each other, and I still remember the photo of the people who were queuing in front of the hospitals.”

“There were so many, and there was a high school girl who was killed after she donated her blood, and on her way back home, she was shot. So, and I wanted to remember this side of humanity and this side of Gwangju. And I started to write the book, and all I wanted to do during the process of writing this book was to experience together, to feel together, and to lend my sensation and body and experience for the killed.

And possibly to reach something I found on the other side of this massacre, possibly light, human dignity, or what can I say? Everything sounds quite cliche, but it was so real for me. So that was what I wanted to do with this book.

It was the process of transformation, myself. I started with human atrocity, but it was like moving on and on to this dignified people. I don’t like the word victim.

It means some kind of defeat, but I don’t think they were defeated. They refused to be defeated. That’s why they were killed.”

“So after that, I wrote the White Book, which is not published in Denmark yet. And in the book, I wanted to write about something. And nothing can harm or destroy.

And it’s inside ourselves. So you can say, I have moved forward, and I myself was transformed during the process. And now I’m thinking of love.

It’s like, suddenly I found the meaning of love. And even if we feel pain, it is the proof of our love. Love is still cliché, sounds cliché, but it is real as well.

So I always move on with the strength of my writing. Hopefully I still move. Definitely Human Acts is the book which has transformed myself the most.

My family doesn’t talk about literature. I mean, we just talk about family things, you know. I interviewed my parents.

I didn’t interview the survivors or people who were injured then, or the bereaved family, because I didn’t want to open their own again. I felt I didn’t have any right to do that. So I just interviewed people around me, my friends or elder friends, colleagues, and my parents as well.”

“So I had to talk to them. I was writing this book about Gwangju, and I remember my father told me, it must be hard on you, but please finish it. I remember these words.

I hope people who read this book could feel the same way I did.

After the set change, the lights come up again slowly. In the center of the stage stands a tall woman in her thirties, her white hem skirt recalling the kind of homespun item worn by mourners. When she silently turns to face the left hand of the stage, this appears to be the cue for a tall slim man dressed in black to emerge from the wings.

He comes walking towards her carrying a life sized skeleton on his back. His bare feet tread the boards with carefully measured steps, as so he fears he might slip in the empty air. The woman now turns to the right, still silent as a marionette.”

“This time the man who steps out from the wings is short and stocky, though in his black clothes and the skeleton on his back, he is identical to the first. The two men glide towards each other from their opposite sides, like images from some old fashioned film, proceeding in slow motion as their projectionist laboriously cranks the handle. They reach the center of the stage at the same time, but they do not pause.

Instead, they simply carry on to the other side, as though forbidden to acknowledge the other’s presence. There isn’t a single empty seat in the house. The front rows look to be mainly made up of actors and journalists, perhaps because this is the opening night.

When Yoon, Suk and the boss had been making their way to their seats and she had glanced to the back of the auditorium, four men in particular had caught her eye. Though they were interspersed among the rest of the audience, she had been in little doubt that they were plain clothed policemen. What’s Mr. Se going to do?

She had thought.”

“When those men hear the lines that the censors scored through, coming out of the mouths of these actors, will they jump up from their seats and rush on to the stage? That chair whirling through the air above the table in the university canteen, the spurts of blood from the boy’s forehead, the cooling plate of curry. What would happen to the production crew, watching the scene unfold from the lightning box?

Would Mr. Seo be arrested? Would he escape only to live a hunted existence, a fugitive whom even his own family would struggle to track down? Once the figures of the men have melted back into the wings, their steps sliding forward with a dreamlike lassitude, the woman begins to speak.

Or so it seems. In actual fact, she cannot be said to say anything at all. Her lips move, but no sound comes out.

Yet, Yoon Sook knows exactly what she is saying. She recognizes the lines from the manuscript where Mr. Seo had written them in with a pen. The manuscript she had typed up herself and proofread three times.”

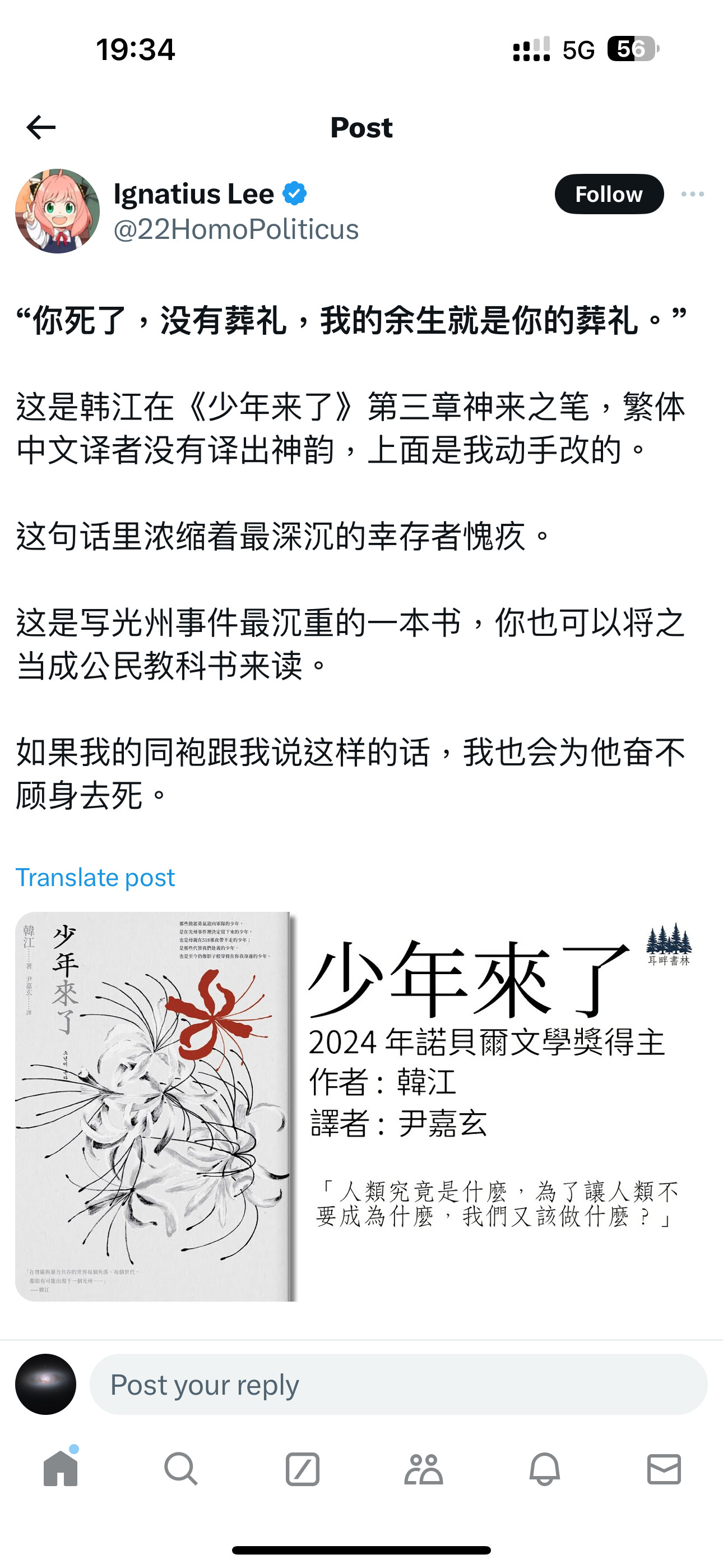

“After you died, I could not hold a funeral. And so my life became a funeral. The woman turns her back on the audience, and the lights go up in the long aisle between the seats.

Now, a strapping man is standing at the end of the aisle, his clothes a tattered hemp. His breathing comes ragged as he walks towards his stage. Unlike the aloof, impassive figures who glided across the stage mere moments ago, this man’s face is contorted with feeling.

He stretches both arms up above his head, straining for who knows what. His lips gupper like a fish on dry land. Again, Yoon Suk can read what those lips are saying, though speech is an uncertain name for the high-pitched sound shrieking out from between them.

Oh, return to me. Oh, return to me when I call your name. Do not delay any longer.

Return to me now. After the initial wave of perplexity has swept through the audience, they subside into cowed silence and gaze with great concentration at the actor’s lips. The lighting in the aisle begins to dim.”

“The woman on stage turns back to face the audience. Silent as ever, she calmly watches the man walking down the aisle, invoking the spirits of the dead. After you died, I couldn’t hold a funeral.

So these eyes that once beheld you became a shrine. These ears that once heard your voice became a shrine. These lungs that once inhaled your breath became a shrine.

Eyes wide open yet seeming not to see the waking world, shrieking up into the empty air while the woman merely moves her lips. The man in hemp mounts the stairs to the stage. His upraised arms swing down, grazing her shoulder as though brushing away snow.

The flowers that bloom in spring, the willows, the raindrops and snowflakes became shrines. The mornings ushering in each day, the evenings that daily darken became shrines.

Flowers blooming in spring, the birch trees, the raindrops and the snow-drops became a shrine.”

“Han Kang visited the Louisiana Museum in 2019, where she was interviewed by Christian Lund, who also produced and edited the interview. Original music for this podcast is made by Bob Pounding. You can watch and listen to hundreds of other interviews with great writers and artists from all over the world at the Louisiana Channel.

That’s channel.louisiana.dk. Or you can find them on YouTube. I’m Pike Malinowski.

Thanks for listening.”

From Louisiana Literature: Han Kang: The Horror of Humanity, May 12, 2021

“我是派克·马林诺夫斯基,你正在收听《路易斯安那文学播客》。我是谁?作为人类的意义是什么?

韩国诗人和小说家韩江用她国家的暴力历史直面这些问题。

从我小时候起,看着人类在历史上和世界各地所犯下的一切就让我感到非常震撼。

韩江在光州长大,这是一个位于朝鲜半岛南部、拥有一百五十万人口的城市。在她和家人搬到首尔不久,光州爆发了一场针对戒严政府的学生起义,成百上千的学生在这场起义中被屠杀。

你知道,人性有着如此广泛的谱系。我一直想知道它的意义。

在这次亲密的访谈中,韩江谈到文学如何帮助她刺穿对人类的怀疑,并谈及她的第六部小说《少年之殇》,这部小说中,12天的屠杀事件是暴力的中心。”

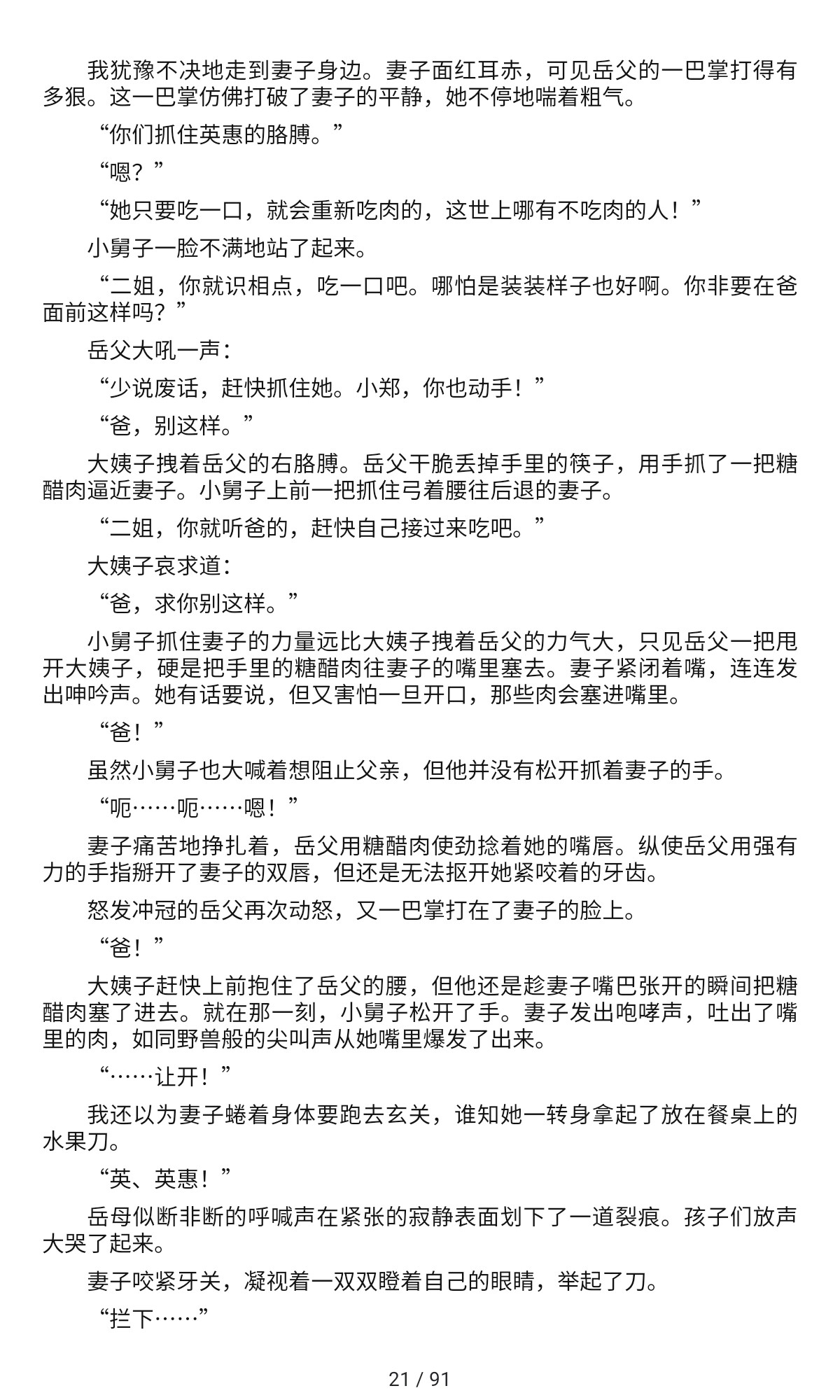

“所以,当我还是个孩子时,我的父亲是一位年轻的小说家。这意味着我们很贫穷,我们不得不经常搬家,我们没有多少家具,但我们有很多书。这就像是一个私人图书馆,就像是被书保护和包围着。

对我来说,书就像是一个生物,不断扩展,因为书的数量在每周、每月地增加,所以就像是与它们一起生活。我上了五所小学,对于一个孩子来说可能有点多。但我不记得自己感到受伤,也许是因为我被所有的书保护着。

我整个下午都在读书,直到我交到朋友。这是一段非常珍贵的记忆。我记得有一天,我在读书,突然看不清行间的字。

我什么也看不见。发生了什么?我意识到天黑了。所以我不得不开灯,然后继续读下去。”

“因此,我发现了书籍纯粹的乐趣。后来,当我成为青少年时,我面临一些很典型的问题,比如,我是谁,我在这个世界上能做什么,为什么每个人都必须死去,为什么人类的痛苦存在,人类是什么,作为人类的意义是什么?然后,我想要探索这些问题,于是我以一种新的方式重新阅读了所有的书,我觉得自己可以说,是在陪伴那些作家们的问题中,一切都变得新鲜了。

某一刻,我想要成为一名作家。我记得那天我决定要成为一名作家。那时我14岁。

我只是想写下我的问题,那时,作家们就像是一个群体,他们包围着我,一起探索和提问,有时他们感到无助、茫然。我只是想和他们在一起,因为我也是无助和茫然的。那时,我开始写一些句子。”

“也许它们像是一些诗。我不确定。我只是写下一些句子或短语,有时甚至只是一些词。

我开始写日记。直到现在,我还在写日记,虽然不是每天都写,但有时会写。就这样。

当时我还没有开始写小说。我从19岁开始写小说,从一个非常短的故事开始。

然后我写了一些更长的故事,并在文学杂志上发表了一些短篇小说。我从大学毕业后,作为编辑和记者工作了三年。

我真的很想写我的第一本小说,所以我辞职了。花了三年时间完成了我的第一本小说。从那时起,我就开始写小说、短篇故事以及诗歌。

所以,我不是刻意要写诗。它们自然而然地出现。即使在写小说时,诗也会自然而然地融入其中。

就像是一种入侵。所以,语言对我来说是我必须一直挣扎的东西,也许要一直到最后。有些问题我思考了很长时间。”

“不,从我小时候起,看着人类的所作所为就让我感到非常震撼。你知道,人类在历史上和世界各地犯下的一切。同时,你也能看到世界各地如此高尚的人们。对我来说,这种对比几乎无法接受。

而且,我是人类的一员,当我们面对人类的恐怖时,我们不得不质问,作为人类的意义是什么。你知道,人性有着如此广泛的谱系。我一直想知道它的意义。

是的,所以,这就像是一场无止境的内心挣扎,因为我想要拥抱这个世界和生活。但当然,有时候我们无法做到,这就像在这两个谜团之间来回走动。这几乎是我的一生。

但是我,我有这种媒介——我的语言,我必须通过它前行。1980年,在朝鲜半岛爆发了一场针对新军政府的戒严令的起义。

而且,国家对反对者进行了屠杀。并且,出现了民间自治。这场事件持续了十天。”

“最终,军队重新回到城市,再次进行屠杀。所以我们可以称之为大屠杀。以及一次绝对的社区。

我看光州,不仅仅是一个特定的城市。对我来说,它更像是一个基本的名字或名词,代表着人类,拥有这些从崇高到恐怖或到最底层的极端。我可以在任何地方看到光州,每当我们面对这两个极端时。

所以我想要写下这个反复出现的光州。我们不知道有多少人被杀害。官方数字是200多人。

但到现在还有许多人失踪。所以我们依然不知道真相。

但你认为有数千人吗?

我认为是的。但我无法确认,因为我们不知道真相。我在光州出生,我的家人在1980年离开了光州。

那是1月份。天气非常寒冷。那是非常寒冷的一天。

所以我甚至记得那天的日期。那是1月26日。我们就那样离开了这个城市,因为我父亲辞去了他的教职。”

“去成为一名全职作家。他说,现在我没有固定的工作了,为什么不去首都生活?这真是一个非常即兴的决定。

我们就搬了。四个月后,光州发生了大屠杀。在此之前,光州只是一个有几所大学的小城市,安静而平和。

突然之间,这个城市的含义完全变了,没有人能想到这场大屠杀。我们可以称之为起义,我们也可以称之为一种绝对的团结的社区。对我们全家来说,这是一段漫长的内疚感。

我们并不是有意离开那个地方,但事实就是如此。所以那种感觉就像是,有些人替我们受了伤害。这个感觉在我心中存了很长时间,即使我从未计划写下它。

我就是在这种我间接经历的记忆中成长的,它一直存在于我的噩梦中。直到我完成了第五本小说后,我突然想捕捉一下,为什么我总是很难接受这个世界或生活的理由。我不得不一次又一次地向内深入挖掘。”

“然后我最终意识到,我必须通过写作来穿透对人类的怀疑。因此,这就是我开始写《少年之殇》的原因。在搜集所有资料的过程中,我更加感到震撼和痛苦,因为我必须目睹所有的暴行。

我阅读了一本很大的证词书,书中记录了900名幸存者、受伤者或失去亲人的人的证词。这就像是把所有的碎片收集在一起,因为我不想写一本冷冰冰的、只记录了事件的书。所以,我读得越多,我就越失去了信任,直到某一时刻,我意识到我正面对那些在暴力面前依然高贵的人们,他们彼此献血,我至今记得那些排队在医院门口的人们的照片。”

“有那么多人,还有一名女高中生,她在献血后回家的路上被枪杀。所以,我想记住人性的这一面,记住光州的这一面。我开始写这本书,在写这本书的过程中,我想要一起体验,一起感受,把我的感知和身体、经历借给那些被杀害的人。

也许能达到一些我在这场大屠杀的另一面找到的东西,也许是光芒、人类的尊严,或者我能怎么形容?一切听起来很陈词滥调,但对我来说,这是真实的。这就是我写这本书时想要做的事情。

这是一个自我转变的过程。我从人类的暴行开始,但它就像不断向前推进,走向那些高贵的人们。我不喜欢‘受害者’这个词。

它意味着某种失败,但我不认为他们失败了。他们拒绝失败,这正是他们被杀害的原因。”

“在那之后,我写了《白书》,但这本书还未在丹麦出版。在书中,我想写一些东西。没有什么能伤害或摧毁这些东西。

而它存在于我们内心深处。所以你可以说,在这个过程中,我向前走了,我自己也在这个过程中发生了转变。现在我在思考爱。

就像是,我突然发现了爱的意义。即使我们感到痛苦,那也是我们爱的证明。爱虽然听起来很陈词滥调,但它也同样真实。

所以我总是带着写作的力量前进。希望我还能继续前进。毫无疑问,《少年之殇》是对我影响最大的书。

我的家人并不谈论文学。我是说,我们只是谈论一些家庭的事情。我采访了我的父母。

我并没有采访幸存者或者当时受伤的人,或者失去亲人的人,因为我不想再揭开他们的伤口。我觉得自己没有这个权利。所以我只采访了我周围的人,我的朋友或者年长的朋友、同事,以及我的父母。”

“所以我不得不和他们谈谈。我正在写关于光州的书,我记得我的父亲对我说,这对你来说一定很难,但请完成它。我记得这些话。

我希望读这本书的人能感受到我所感受到的。

当布景转换后,灯光再次缓缓亮起。舞台中央站着一位三十多岁的高个子女子,她白色的裙摆让人联想到哀悼者穿着的那种手工制品。当她默默地转向舞台左侧时,这似乎是给一位从幕布后走出的高瘦男子的信号。

他背着一个真人大小的骷髅走向她。他赤脚走在舞台上,每一步都小心翼翼,仿佛害怕在空中滑倒。女子现在转向右边,依然像个木偶般的沉默。”

“这一次,从幕布后走出来的男人又矮又壮,虽然他穿着黑色的衣服,背着骷髅,但与第一个人完全一样。这两个人从各自的方向滑向彼此,就像是某种老式电影中的影像,他们慢慢地向前,投影员费力地摇动着手柄。他们在舞台中央相遇,却并没有停下脚步。

而是继续朝对方的另一侧走去,仿佛被禁止承认对方的存在。观众席没有一个空位。前排似乎主要是演员和记者,可能是因为这是首演之夜。

当尹淑和老板正走向座位时,她瞥了一眼礼堂后方,注意到四个特别的人。尽管他们与其他观众混杂在一起,但她几乎毫无疑问,他们是便衣警察。‘徐先生会怎么办?’

她这样想着。”

“当那些人听到那些被审查者删去的台词从这些演员的嘴里说出来时,他们会不会从座位上跳起来,冲上舞台?那张在大学食堂内空中旋转的椅子,男孩额头上的血花,以及逐渐冷却的咖喱盘。剧组在灯光箱里观看场景发展的过程中会发生什么?

徐先生会被逮捕吗?他会逃脱,却不得不过着逃亡的生活吗?他的家人甚至也难以找到他的踪迹吗?当这些人的身影融回到幕布后,他们的脚步如梦般懒散地向前滑动,舞台上的女子开始说话。

或者说好像如此。事实上,不能说她真的在说话。她的嘴唇在动,但没有声音传出。

然而,尹淑完全明白她在说什么。她认得那些台词,是徐先生用笔写在手稿上的台词。那份手稿是她自己打出来的,还校对了三遍。”

“‘你死后,我无法为你举行葬礼。所以我的生命变成了葬礼。’女子背对着观众,长长的通道间的灯光亮起。

这时,一个身材魁梧的男子站在通道的尽头,他穿着破旧的麻布衣物。他呼吸急促地走向舞台。与之前那些冷漠、面无表情地滑过舞台的人物不同,这个男人的脸上充满了情感。

他高举双臂,仿佛在奋力抓住某种东西。他的嘴唇像是濒死的鱼在挣扎般开合。尹淑依然能读懂这些嘴唇所说的,尽管这无法被称为‘说话’,更像是从他嘴中发出的高亢尖叫。

‘哦,回到我身边。哦,当我呼唤你的名字时,回到我身边。不要再迟疑了。

现在就回到我身边。’当最初的困惑席卷过观众席后,他们沉默下来,专注地凝视着演员的嘴唇。通道里的灯光渐渐暗下。”

“舞台上的女子重新面向观众。依旧沉默,她平静地看着那位在通道中走来的男子,他正在召唤死者的灵魂。‘你死后,我无法为你举行葬礼。

所以那些曾经看到你的眼睛变成了一座神龛。那些曾经听到你声音的耳朵变成了一座神龛。那些曾经吸入你呼吸的肺变成了一座神龛。’

眼睛睁得大大的,却似乎看不见这个醒着的世界,对着空中尖叫,而女子仅仅只是默默地动着嘴唇。身穿麻布的男子登上了舞台。他高举的手臂垂下,轻轻擦过她的肩膀,仿佛拂去落雪。

‘春天开花的花朵、柳树、雨滴和雪花变成了神龛。每一天的清晨和每一天变暗的傍晚都变成了神龛。

春天盛开的花朵、桦树、雨滴和雪滴变成了一座神龛。’”

“韩江在2019年访问了路易斯安那博物馆,并接受了克里斯蒂安·伦德的采访,伦德也是这次访谈的制片人和编辑。本播客的原创音乐由鲍勃·庞丁创作。你可以在路易斯安那频道观看和聆听来自世界各地的作家和艺术家的数百场访谈。

访问channel.louisiana.dk。你也可以在YouTube上找到他们。我是派克·马林诺夫斯基。

谢谢收听。”

摘自《路易斯安那文学》:韩江:《人性的恐怖》,2021年5月12日